Ng Lai Huat, a 68-year-old human resource manager and award-winning photographer, thinks he’s more or less achieved all his dreams — to retire healthily and have a happy family.

Just one remains: he wants his only son to “faster marry!” because he hopes for his son to have a good family too.

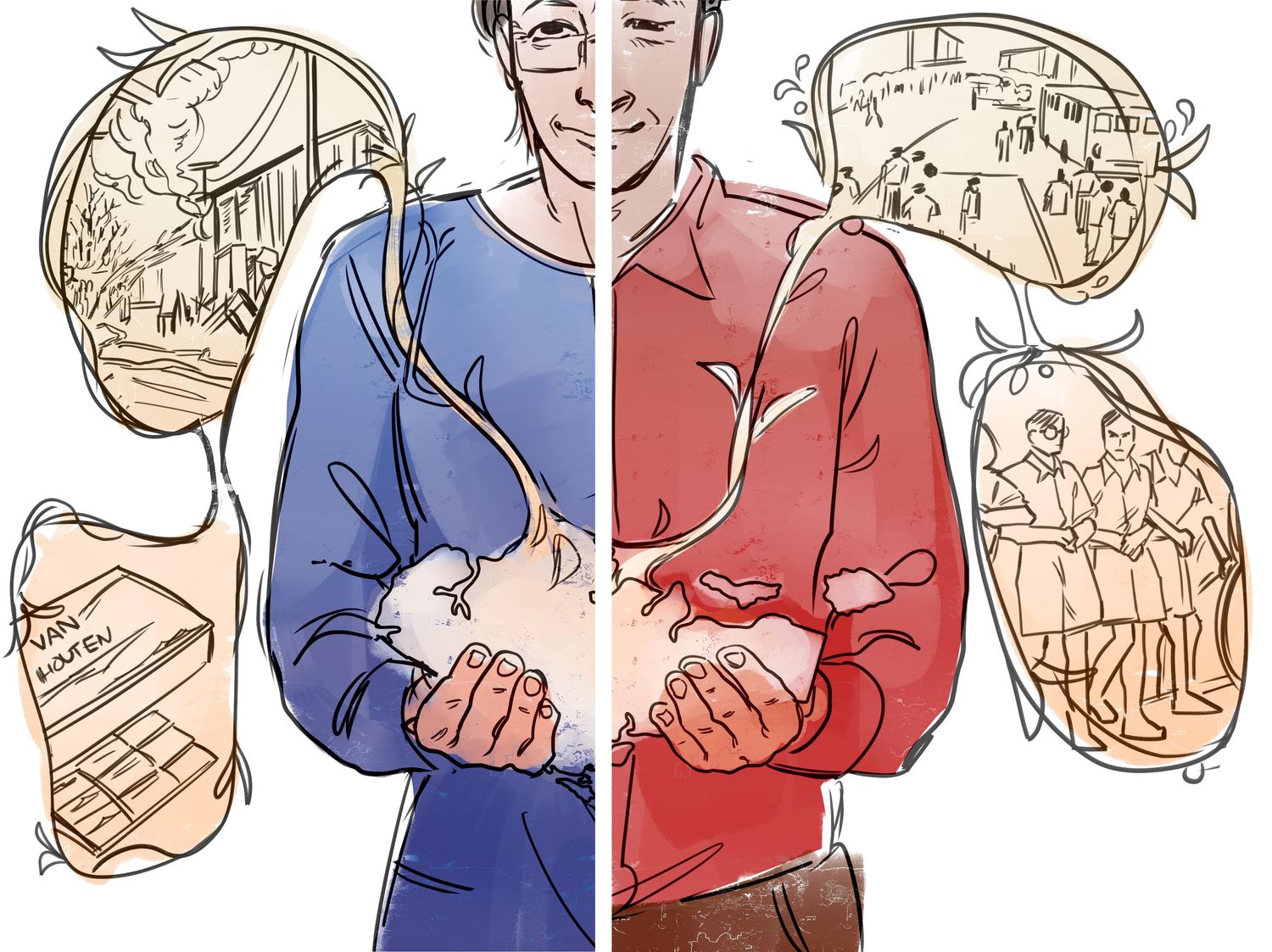

Koh Siew Har, 65, has had decades of experience in the optical lens industry, from working as a lab technician to her current job of overseeing quality assurance and distribution, and feels that she has led a fulfilling life.

More than optical lenses and photographs, their experiences tell the story of triumph over hardship, of love and loss.

You don't turn your back on family

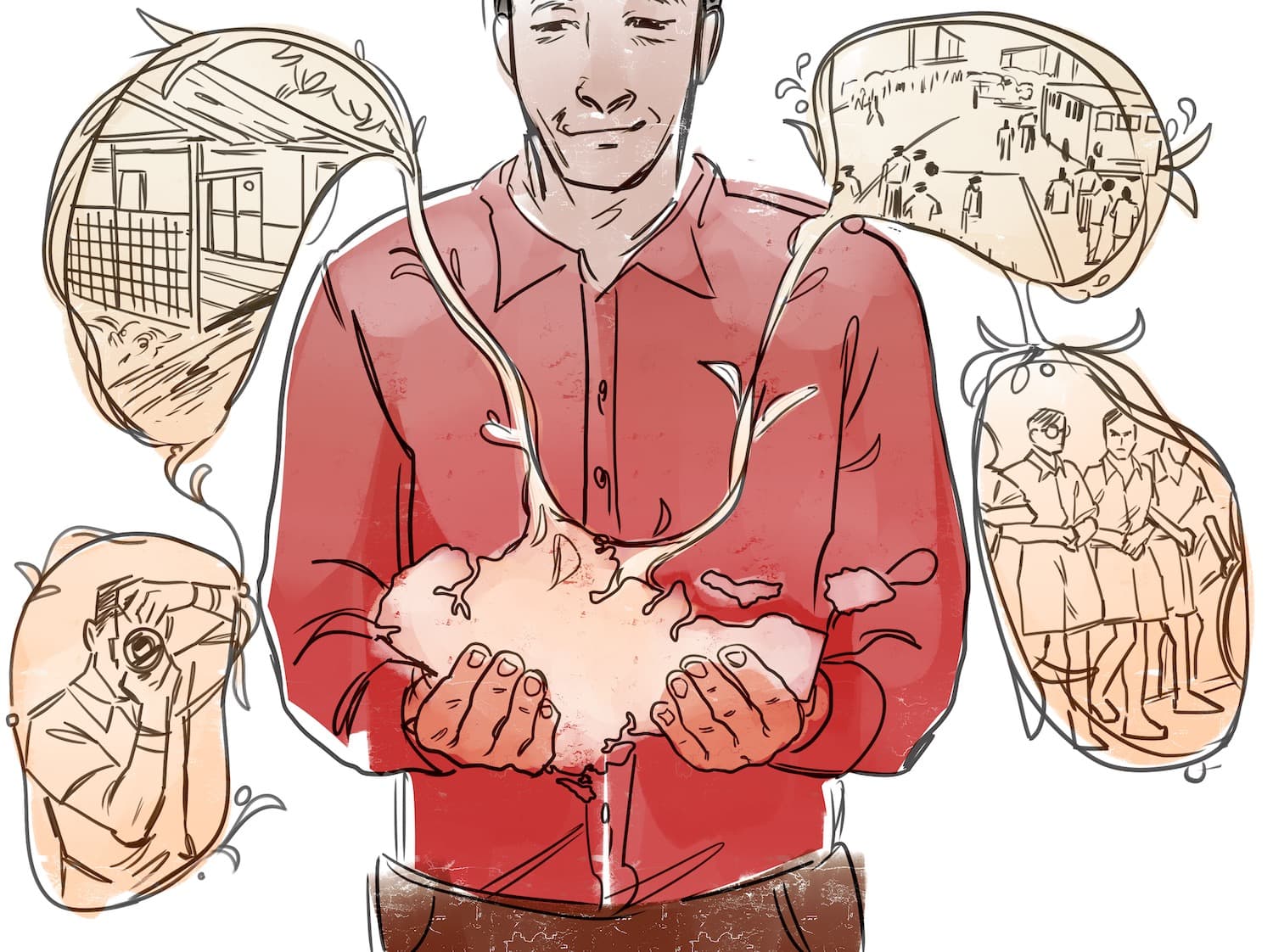

Lai Huat is most proud of his happy and healthy family. When asked about achievements more personal to him, he responds without hesitation that he’s a law-abiding and hardworking citizen. To him achievements seem defined by how he relates to the others, family and country.

A community-conscious person, he advises, “As long as you’re law-abiding and you respect your country, you will be respected, too. That has been my experience.”

Siew Har, too, is proud of her accomplishments. While she humbly shares her pride for having purchased her own condominium apartment, she is far more stirred by her having taken care of her parents to a ripe, old age.

She clarifies that it is not only about children caring for parents — the reverse should be equally emphasised. “Parents will always support [their kids and even grandchildren]. Help them buy resale flat, or pay for the wedding. It’s not just money, but moral and spiritual support.”

Perhaps this familial appreciation was forged in the fires — some literal, some not.

A durian city of a prickly past but sweet fruit

“I was a victim of the Bukit Ho Swee fire in 1961. I was only 5 years old,” Siew Har recounts. As her shell-shocked mother and grandmother hurriedly rushed the children somewhere safe, their entire attap house was being ravaged, consumed by angry blazes and smoke. They lost everything, save a bag of paper containing birth certificates and other important documents.

Families like theirs were relocated to a primary school compound, living off food rations. Siew Har’s family would later find themselves sharing a small two-room HDB flat with a relative, which was as far as they could afford for rent.

Lai Huat was fortunate not to be near the fire. Describing his childhood as plain sailing, however, would be inaccurate.

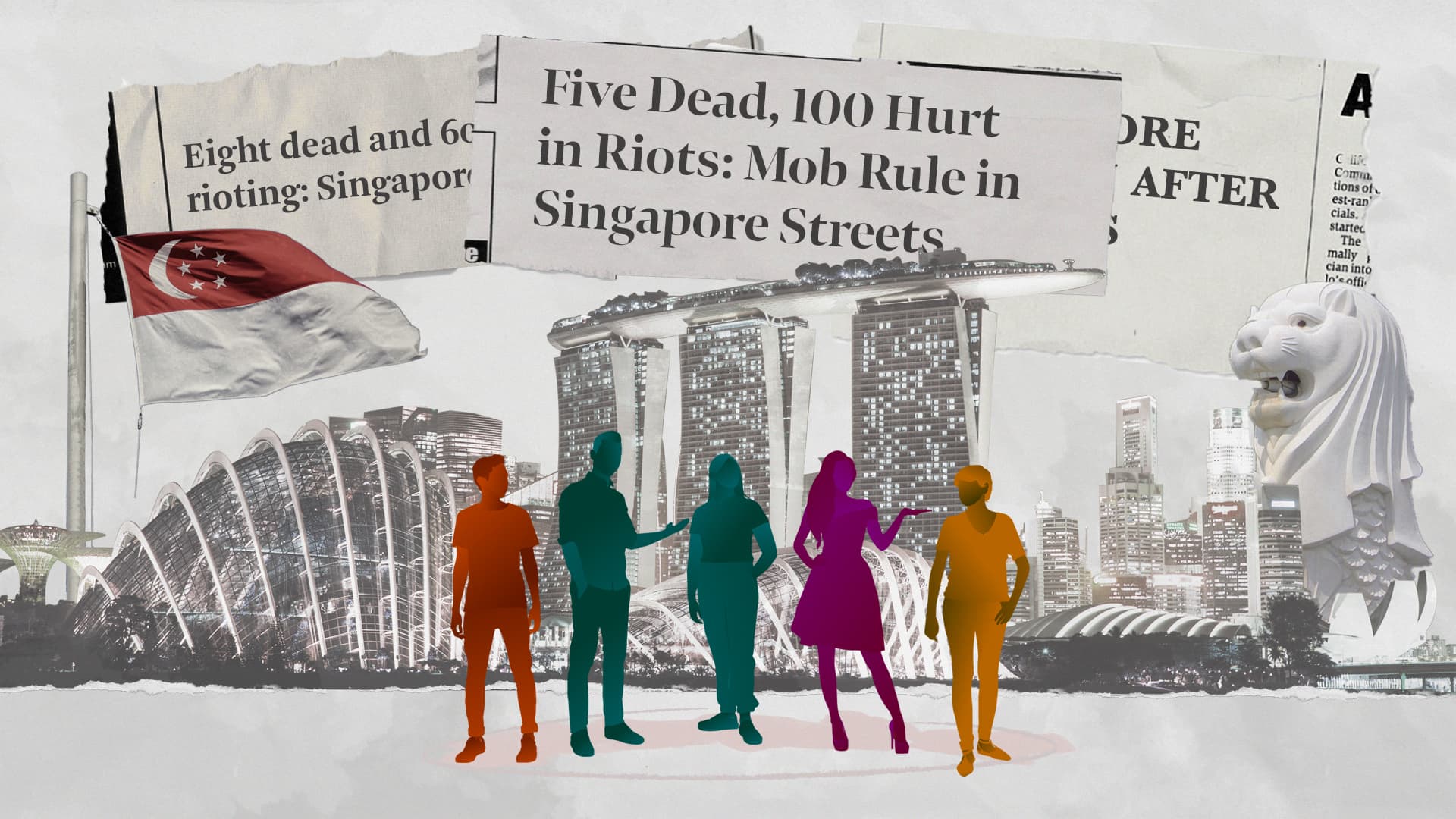

Recalling the race riots of the 1960s, Lai Huat says, “There were rumours of Malay people killing Chinese people.” As a child, he anxiously watched the adults pick up parangs and shotguns to keep watch of the kampung each night.

With each crisis, the government would not only fix, but improve, the situation. HDB flats were urgently built to replace razed homes. Racial tensions were diffused and a multiracial policy put in place following the riots. Aggressive development of the country saw people’s quality of life soar.

“Singapore is always improving,” Lai Huat says. “This is by far my generation’s greatest pride … I love this piece of land where I belong, where we have worked hard for everyone.”

When policemen wore shorts and we had kampung spirit

Still, some things are lost with constant change.

Siew Har reminisces, “When you cook something, you share it. Everyone is family. If a neighbour goes to Chinatown, she’ll take orders, like chicken meat or sweets.”

“Last time, you don’t need to lock your house when you sleep. It was very easy to connect and help each other,” Lai Huat concurs. He considers the shift to HDB and a booming population the reasons why people now lock their doors. To him, the buildings seem more foreign today.

Siew Har, too, feels that people are more disconnected now, especially with the rise of technology. She worries about where our modern abundance is taking us. While she had held herself back from buying her favourite Van Houten chocolates in the past, people now can “eat until sian”.

From their perspective and experiences of growing up through many tribulations, people nowadays seem to take for granted what they have.

I’m fired up, don’t shut me down

It is little surprise, then, that our golden-age compatriots are not yet ready to fully retire even after years working and caring for their family.

Outside his full-time job, Lai Huat teaches photography and vegetarian cooking at the community centre, seeing them as his continuing contributions to Singapore.

Siew Har, too, chooses to keep working, and wishes to do social work if her “boss says it’s time to retire”.

At the conclusion of our chat, Siew Har expresses a wish that younger Singaporeans will be more mindful with what they say or do, especially with regards to their family.

As for Lai Huat, he hopes that the future generations will “be pragmatic, resilient and continue learning”. He thoughtfully adds: “Have dreams and ambition, too."