What makes Singapore tick? We know it is small, lacks natural resources and was at some point a “sleepy fishing village”. We also know it does tick, efficient as the Rolex watches that don the wrists of many residents in the small country — demonstrating a degree of prosperity that may be surprising, given that the country’s conditions seem to predispose it to a fate of insignificance.

How did we overcome these limitations?

A young person’s dread of receiving the “On Government Service” letter from MINDEF, our defined education streams and that voice in your head asking, “Can say or not?” before posting anything online — these disparate things have something in common: they were all solutions engineered by the city state to overcome its history of vulnerability.

Small fish, big ocean

In the nation’s early years, its economy was small and undeveloped, compared to its regional neighbours’. Using a helpline, Singapore reached out to the United Nations (UN). In 1961, the UN responded with a document known as the Winsemius Report, which argued for Singapore to focus on international trade. The Economic Development Board (EDB) was established that same year to implement these policy recommendations.

Since then, Singapore has been somewhat of a socialite: Singapore has entered into hundreds of FTAs with other nations and is a member of multiple regional organisations, including ASEAN and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

Today, Singapore is on good diplomatic terms with just about any nation, a fitting quality of Asia’s financial hub.

The lethal red dot

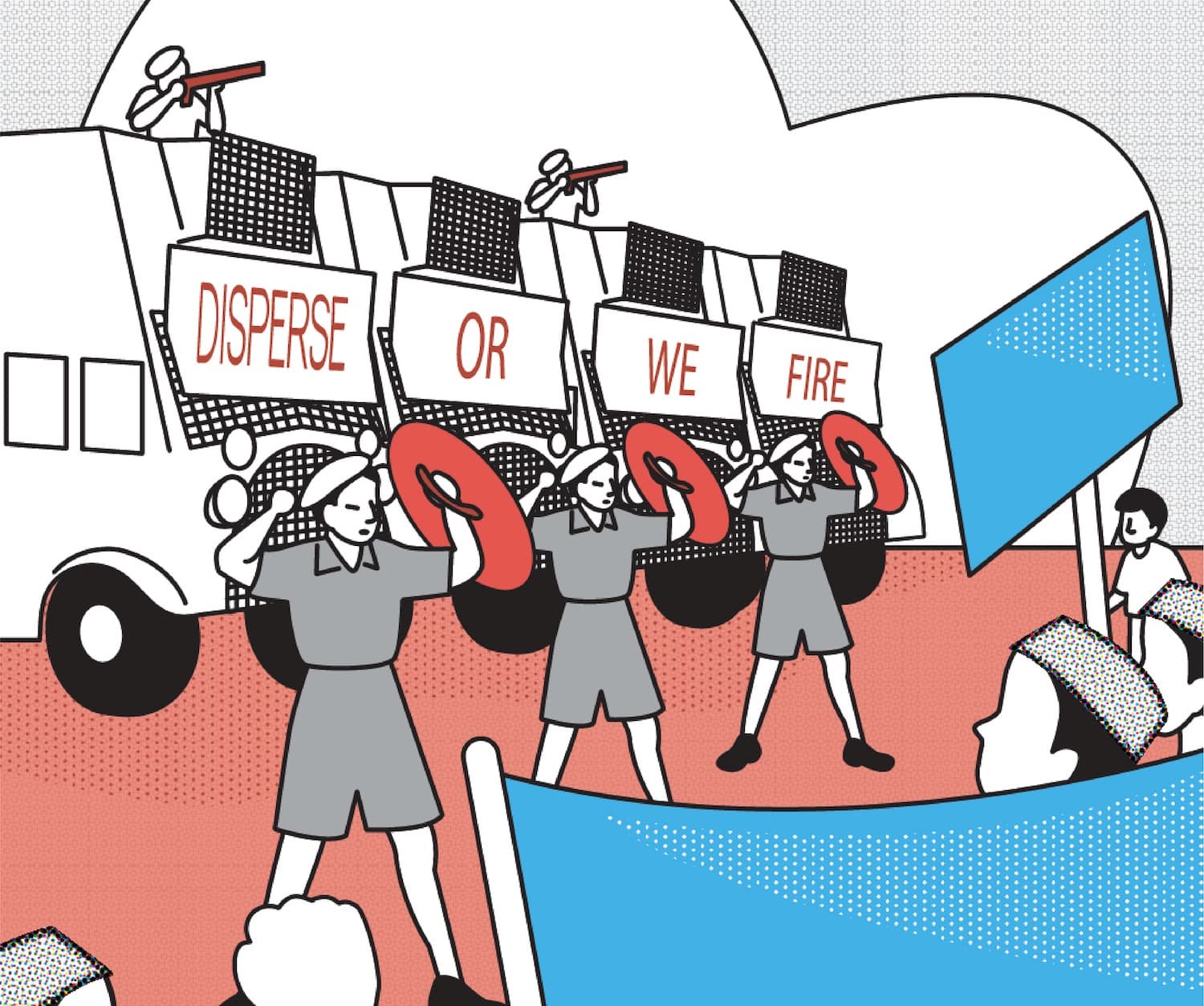

Throughout the 1960s, Singapore was painfully reminded of its small size and lack of defence infrastructure. From 1963 to 1966, Indonesia launched 42 terror attacks in Singapore, aiming to prevent what it perceived as an expansion of colonial power in the region. With just a small volunteer defence corps that was not adequately equipped, Singapore could not stop the attacks then.

Thereafter, the small nation, refusing to be helpless again, established the Ministry of Interior and Defence in August 1965. Today, we know it as the Ministry of Defence.

Through the decades, the ministry has turned the island into a military powerhouse with the best air force and navy in Southeast Asia. This accomplishment is partly thanks to the ministry’s heavy investment (up to S$15.36 billion in 2021) in acquiring and developing military technology to ensure Singapore’s defence readiness.

Given its small population, Singapore’s mandatory military service is also an essential component of its armed forces, demonstrating how every Singaporean has a part to play in the nation’s survival.

Having politics in small spaces

In Singapore’s early days, the military answered not only to the issue of interstate conflict, but also of internal security.

Amidst rising interracial friction in the 1960s, racial riots erupted, necessitating the involvement of the armed forces.

These riots were not the only sobering conflict of differences within young Singapore. In 1963, Operation Coldstore saw the arrest of over 100 people for suspected communist sympathies. These people, among whom were 24 leaders of the Barisan Sosialis party — Singapore’s largest opposition party then — were detained without trial.

With the Barisan Socialis no longer in the political landscape, the PAP was able to push for stricter labour discipline. Trade unions were co-opted by the state and a culture of hard work and thriftiness was instilled. Most of these measures still exist today, such as the National Trades Union Congress and the Central Provident Fund scheme.

To enforce social stability, racial harmony was enshrined in legislation. Globally, sedition laws tend to outlaw the incitement of violent rebellion against the state. Singapore’s sedition law goes further: it is the only in the world that considers the promotion of enmity between races as seditious.

Political processes were also controlled. Since the 1986 Legal Profession (Amendment) Act, the Law Society is unable to comment on legislation, which means that laws tend to pass in Parliament without the wider involvement of legally trained professionals. Singapore’s constitution prioritises national security over all other interests, including freedom of speech.

Watch out

Singapore’s smallness arguably played no small role in its success today. These limitations and vulnerabilities forced us to take risks, overhaul infrastructure and completely rethink what it means to be a small country.

Across our 57 years of independence, we have proven, time and again, that we can build a small nation that rivals geopolitical titans more than 10,000 times larger than us in land mass — like a Rolex watch more intricate, precise and valuable than a clocktower.

Sources: BBC, The Diplomat, Insider, MINDEF Singapore, National Archives of Singapore, National Library Board (1, 2, 3, 4), Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, The Straits Times (1, 2, 3)