Uniquely Singapore

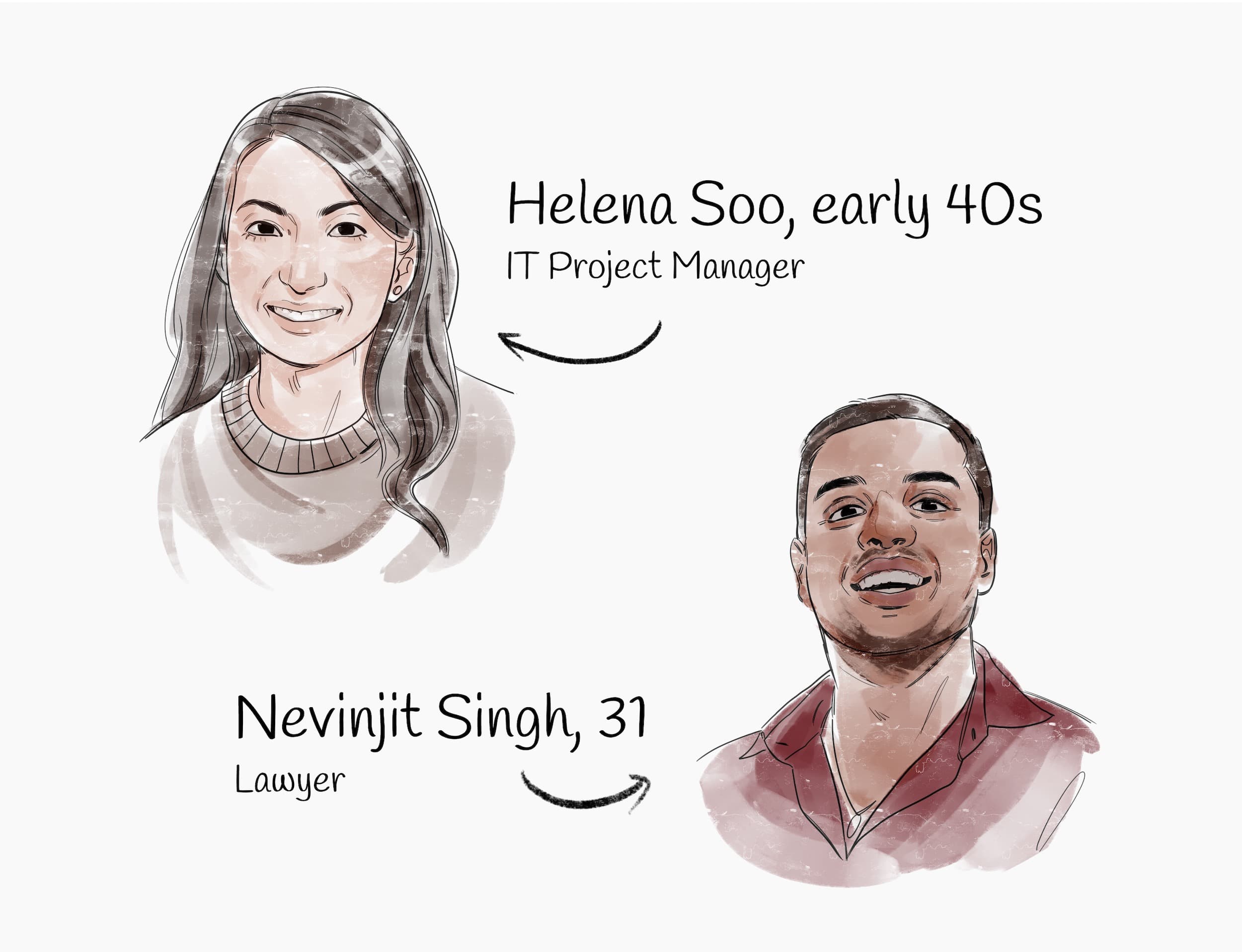

“I have to be PC [politically correct], right?” was how both Helena Soo, an IT project manager in her early 40s, and Nevinjit Singh, a 31-year-old lawyer, started our interview. As quintessentially Singaporean — demonstrated by their opening salvo — mid-career professionals, Helena and Nevin share with us what it’s like to grow up and forge a career in this country.

The sandwich generation

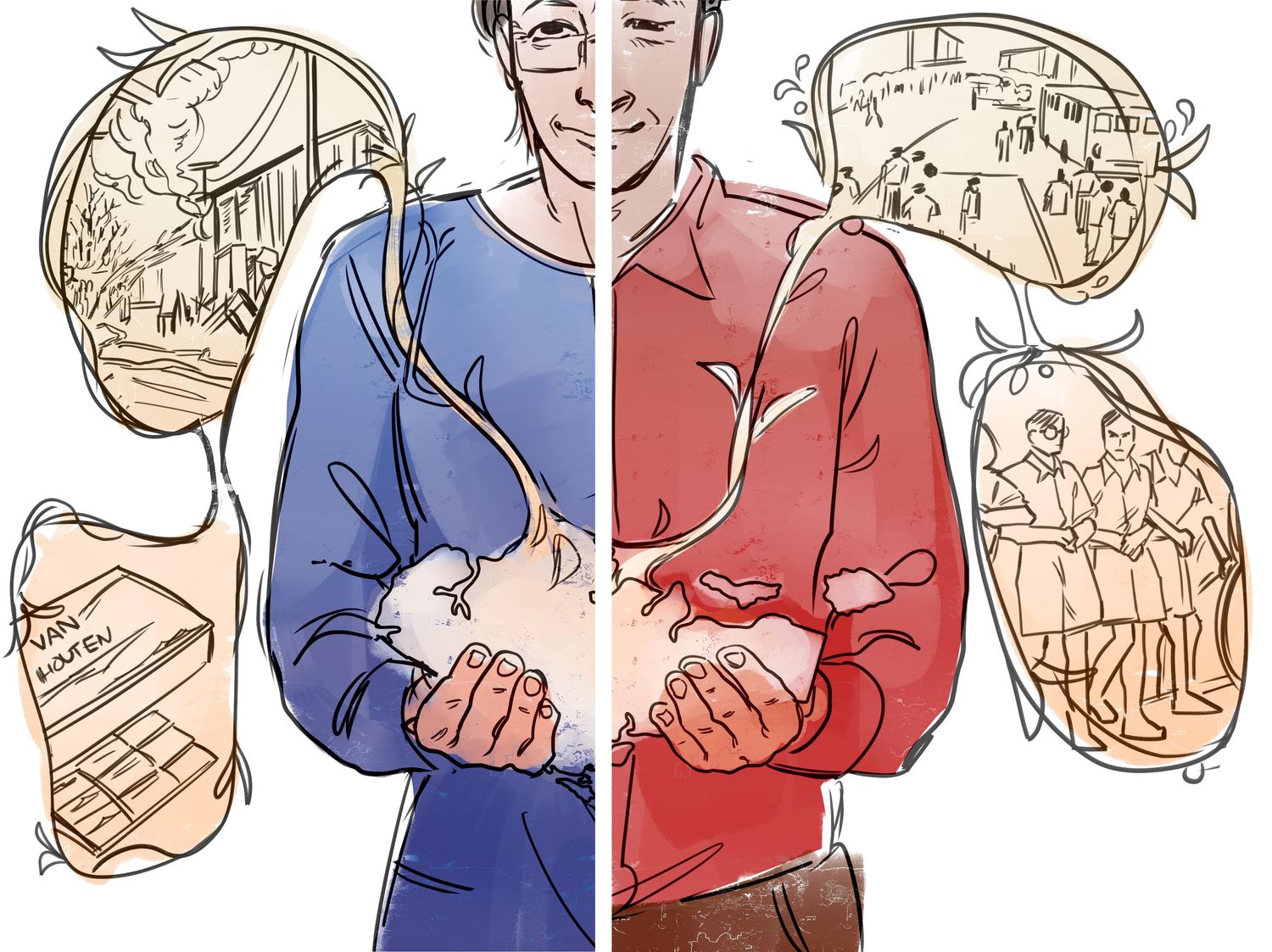

Helena considers the people in their 30s to late 40s resilient. “Previously, so long as you go to a university … you can get a position easily.” Moreover, without a dense population and stiff competition, her parents’ generation seemed more relaxed when it came to work.

“But for our generation, going to uni is common,” she explains. Now, it’s a “rat race” — she concludes “that’s why our generation is always working for others.”

On the other hand, Nevin considers those in their 30s to have a life that’s easier than not. “We haven’t seen things like war [and] recession … More pampered, I guess”. He elaborates, “Everything’s planned for you — just go and do it.”

The expectation that all Singaporeans should go to university weighs heavily on them. While they recognise that a university education gives them opportunities, it can also be stifling, like many opened doors all leading to the same place.

Great expectations

Being a Singaporean undoubtedly has its benefits. Nevin noticed that when he was studying in the UK, people “recognised that if you’re from Singapore … you have a standard. People invest more in you.”

Unfortunately, Nevin has also seen the darker underbelly of this unyielding standard. Growing up, he had what he called the “honour of having many one-to-one conversations with teachers, discipline masters and counsellors”. Once, a teacher told him and his parents that he would end up in jail if he continued his youthful mischief.

Ironically, the expectation that Nevin would remain a delinquent still weighs on him. “When you decide you don’t want to follow [your parents or norms], it’s seen as being a bit of a rebel” — even if you surpass these expectations, Nevin observes.

“The challenge is actually convincing [people] that ‘Hey, I’m not kidding, I’m actually a lawyer.’” Having only limited, planned paths growing up in Singapore, people do not expect a naughty kid to have suited up like that.

Condemned if you continue your mischief, misunderstood if you do not — in Nevin’s experience, people in Singapore might not see you for who you are, but what you ought to have been.

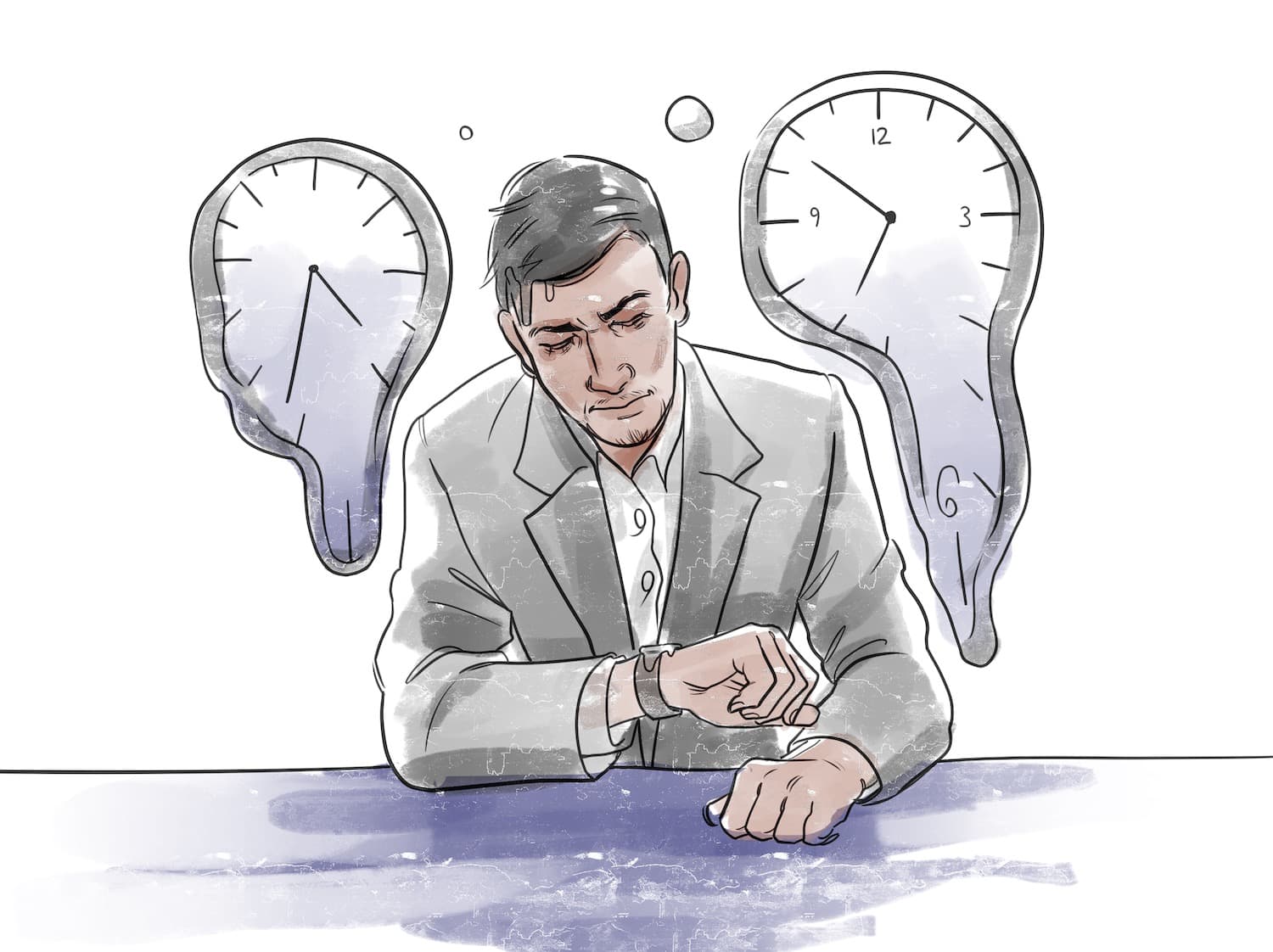

Burnout is an occupational hazard

Helena tells her own anecdote on expectations. Earlier in her career, Helena found herself eager to do her best, resulting in burnout. Even though she is better at managing her expectations now, office politics still sometimes leave her feeling like she’s part of a “K-drama”.

She recounts, “My boss told me, ‘Helena, you are a very good lead, but every time you joke in a meeting, people don’t take you seriously.’ I thought I was just trying to ease the pressure.”

For Nevin, “staying awake” is his biggest challenge at work, he quips. Yet even after work, he laments not being as productive as he wants to. “If it’s a whole week of non-stop work, when it comes to a day off, nothing productive happens that day … I just shut down.”

He thinks that it’s easy to get bored here in small Singapore, too. With a hard-work culture, he reasons that Singapore may not be “a very good place for mental health of people.”

Singaporever after?

While Nevin observes that issues of mental health are simply not spoken about, he admits that Singapore is a good place to work and have a family. “Sink your roots when you want to have a stable — certain people call it mundane — life.”

While he hesitates on whether he has established a life here, he ultimately believes that this is his home, “for better or for worse”, and would choose Singapore over anywhere else.

Helena, on the other hand, is someone family-oriented as she is, in her own words, “married with two kids, peacefully or not — not too sure”.

“I definitely am very sunken in. Because I do not see my parents going anywhere. My siblings, as well, they will be here and I really want to be with them.” When she took a break from work, it was her family who supported her.

Helena also enjoys the structure here. Citing the government’s commitment to continuous learning, she explains how there are now many courses available to working adults, like “how to manage yourself [and] your emotions.”

These played some part in revising her idea of success: instead of a beautiful family in a big house with a big car, she now seeks job satisfaction and time with her closely knit (and still beautiful) family.

Nevin reflects a similar sentiment that he is not looking for a big house or a big car. It seems that somewhere along the way, Singaporeans have dropped the 5 Cs in favour of more authentic goals, shedding the expectations that have been placed on them.

Nevin hopes that his generation’s successors forge their own path. “Whether it’s here or overseas, this country needs more people who grow up doing what they want to do.”