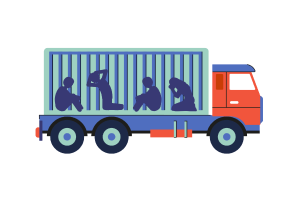

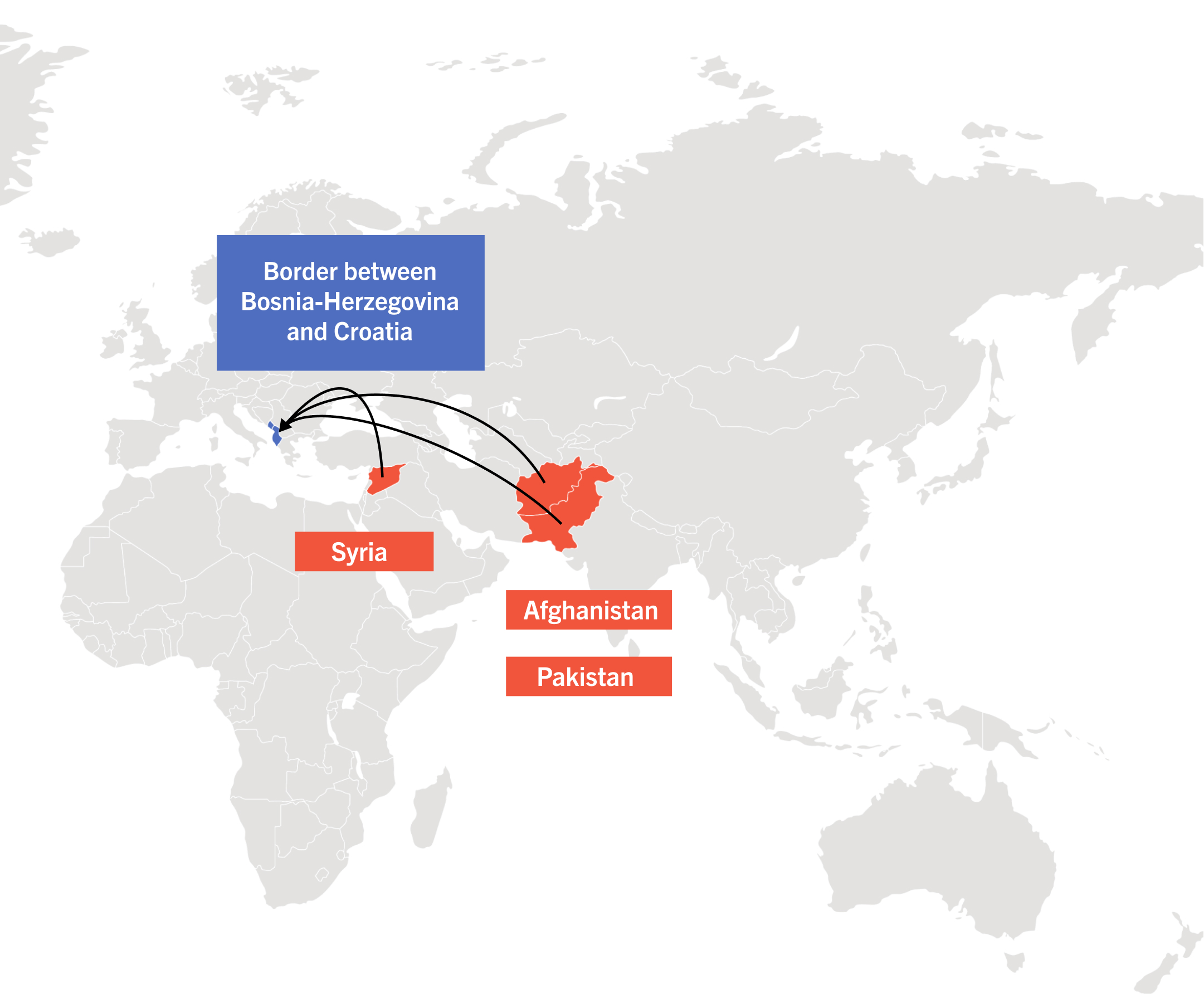

Twenty-one-year-old Afghan migrant Morteza Mohammadi lives in a destroyed factory in Bosnia-Herzegovina. He is waiting to make his seventh attempt to cross into European Union (EU) via Croatia, where he can seek asylum from the conflict ravaging Afghanistan.

On the other side of the Mediterranean Sea, Ahmed, an unemployed Tunisian, is also planning to make an illegal crossing into the EU. His home country, Tunisia, suffers from high unemployment rates, and he hopes to find a job in Italy.

Mohammadi and Ahmed are just two of the many migrants who make a perilous journey away from home in search of a better life. Yet, this already-difficult journey is made more arduous by the pandemic, in ways that the world is only beginning to understand.

A pandemic-worsened plight

COVID-19 has severely crippled the resources available to migrants, and exposed their precarious position in their adopted country.

Asylum shelters are turning away migrants like Mohammadi out of fears of infection. Yet, migrants already in refugee camps, like the Rohingyas in Bangladesh, are also reporting increased violence and hunger because of COVID-19 lockdowns.

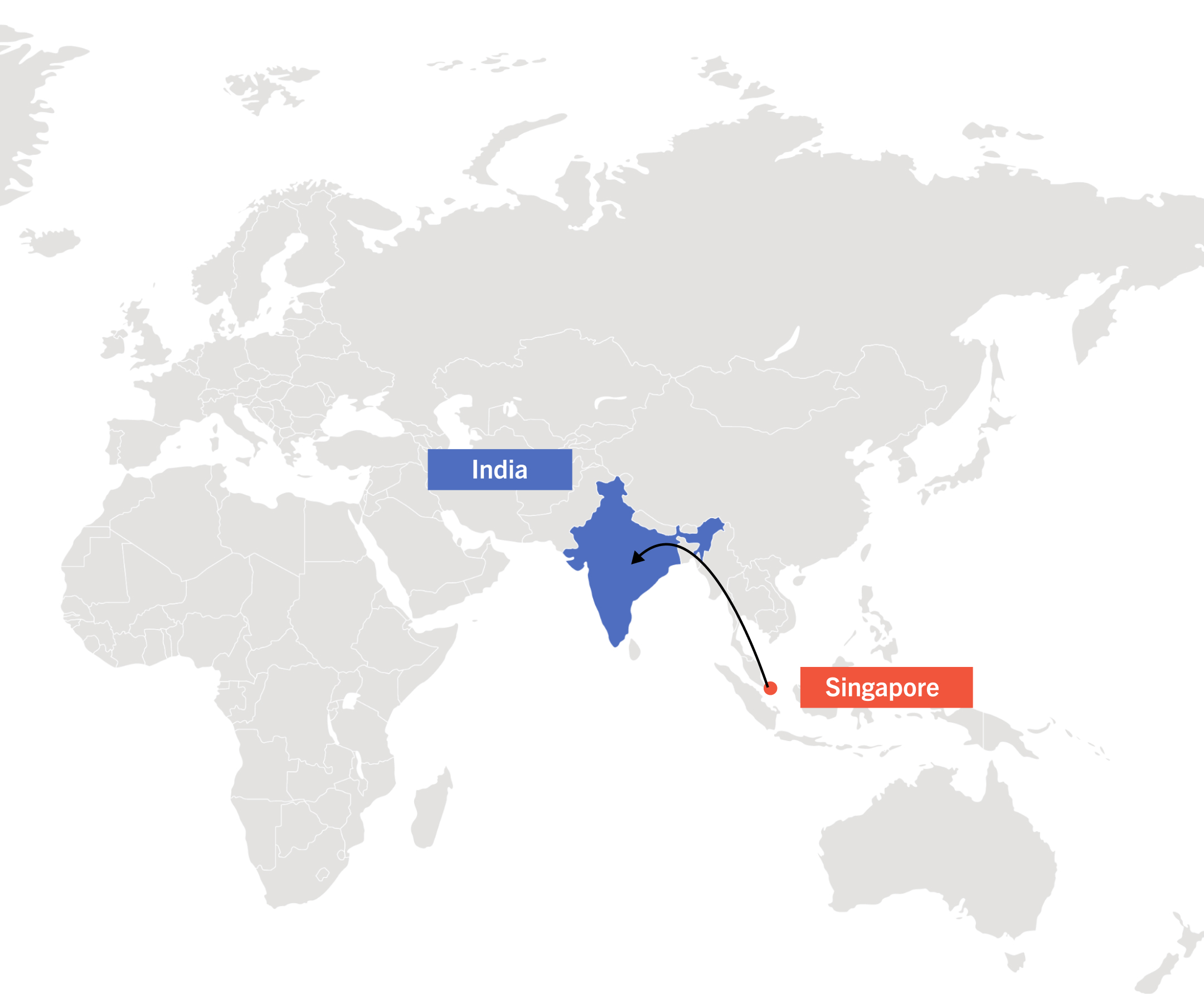

Additionally, a study by the World Bank found that migrants are almost twice as vulnerable to unemployment during economic crises as non-migrants.

In these dire circumstances, migrants like Ahmed, desperate to escape poverty, make the difficult and illegal trek into richer countries where they face even more hardship. Other migrants have lost their jobs and are forced to return home, creating a “backflow” of migration to home countries ill-equipped to reintegrate them.