Since April 2017, up to two million Uighurs and other Muslims have been detained in re-education camps in Xinjiang, where they are reportedly forced to memorise Communist Party propaganda and renounce their religion.

Yet, even after rejoining society as “reformed citizens”, Uighurs are still closely surveilled and controlled by the Chinese state.

The Uighurs in China

The world’s largest population of Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic group, live in Xinjiang. They see themselves as culturally and ethnically closer to the people who live in Central Asia, rather than the Han Chinese who are China’s ethnic majority.

In 1933, the Uighur leaders declared an independent Republic of East Turkestan, but it was reabsorbed into Communist China in 1949. The region then saw a mass migration of Han Chinese, which led to a build-up of anti-Han and separatist sentiment.

In 2009, a violent dispute between migrant Uighurs and Han Chinese workers in Guangdong, triggered by an accusation of sexual assault, left at least two Uighurs dead. It subsequently incited a series of anti-Chinese rioting in Ürümqi, Xinjiang’s capital. The riot killed around 200 people, believed to be mostly Han Chinese.

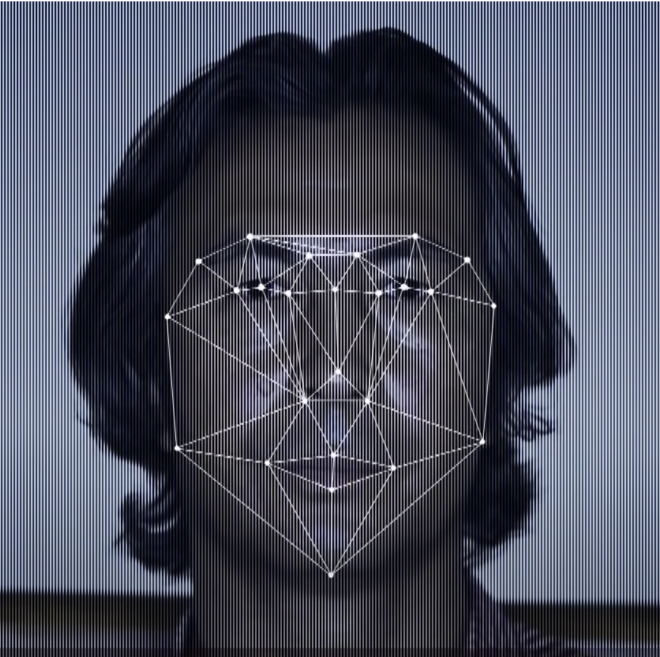

This incident marked a turning point in Beijing’s attitude towards Uighurs. Since then, thousands of security personnel have been recruited to routinely stop and search Uighurs at checkpoints, and artificial intelligence (AI) has been employed to shore up China’s burgeoning surveillance apparatus.

China’s algorithms of repression

Oppressive surveillance technology systems collect data and send them to a centralised database, the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP). The authorities can then use this data to profile and control the Uighurs more insidiously.